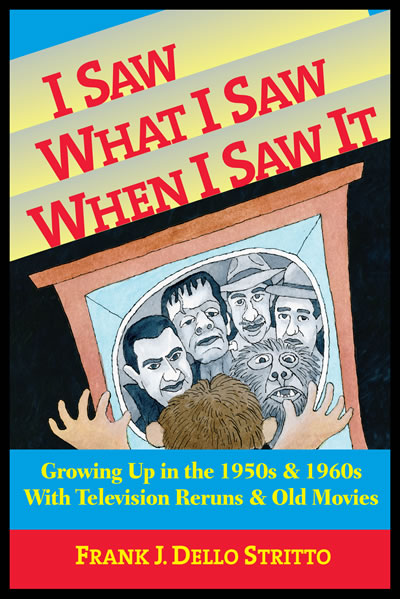

I SAW WHAT I SAW WHEN I SAW IT

Growing Up in the 1950s & 1960s With Television Reruns & Old Movies

PREFACE

Chick: Quiet, they’re after me.

Talbot: After you? What for?

Chick: McDougal was almost killed last night by either a wolf or a man wearing the mask of a wolf.

Talbot: It was a wolf. I am going to give myself up. It’s the only way to clear you.

Chick: Then you were on the level about that wolf business?

Talbot: Yes, I’m going to surrender.

Chick: Wait, you can’t do that. Dracula is taking Wilbur and Joan to the island.

Talbot: Are you sure of that?

Chick: I saw what I saw when I saw it.

Talbot: Hurry, follow me…

Throughout Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, Chick (Bud Abbott) scoffs at the existence of monsters. His bumbling buddy Wilbur (Lou Costello) insists “I saw what I saw when I saw it,” but he is ignored, and mocked. Talbot (Lon Chaney, Jr.) enlists Wilbur in his battle against Dracula (Bela Lugosi). Much of Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein is a tug-of-war between Chick and Talbot for Wilbur’s soul. Chick at last accepts the fantastic, realizes that Talbot is a werewolf, and repeats Wilbur’s mantra “I saw what I saw when I saw it.” He joins Talbot to thwart Dracula’s plan to transplant Wilbur’s brain into Frankenstein’s Monster.

The Monster can never grow old. Wilbur, whether he keeps his old body or gets a new one, will never grow up. He will always be the lovable, comical, little man known so well to my generation.

Wilbur Gray is a typical Lou Costello character. Everyone can empathize with him, because all of us at some point in our lives are like him: innocents in a world of larger, stronger, wiser, often not too compassionate people. Most of us outgrow that phase. Wilbur and Costello’s other characters never do.

This book is about growing up in America—in New Jersey to be exact—in the 1950s and 1960s. It is a personal history, but one which, with some variations, is shared by many Americans of my age. It is a marginal history, and might be a trivial history but for a coincidence of timing. The postwar baby-boom generation and television—two pivotal components of 20th-century American culture—came of age together, and each helped shape the other. Watching television, and later going to the movies, certainly shaped me.

* * *

Much of a young person’s life is like Wilbur Gray’s, an ongoing struggle simply trying to figure things out. We tend to imitate what we see, by watching our parents, family and friends, or by watching television.

Imitation starts early, and we have no memory of learning the most basic skills. I have vague recollections of learning to read and write, none at all of learning to talk or walk. I have no memory of first crawling to our old television set and turning its channel dial. On most 1950s televisions, the dials and knobs stand maybe two feet above the floor and pose some challenge to a very small child. Perhaps the need to reach them accelerates my ability to stand erect.

Among the early tasks that I have no memory of first learning is reciting the Lord’s Prayer. At the start of every school day, I and my classmates, like millions of children across America, struggle through the King James phrases. We learn the prayer long before we can read, and never think much about what we are saying. Only years later do I come to understand “hallowed be thy name,” or “forgive us our trespasses.” Reciting the phrases is a daily ritual, something that I do each day. The prayer always ends with a phrase I do not understand, “lead us not into temptation.”

There once was a boy—maybe an urban legend, but I believe in him—who like the rest of us recited The Lord’s Prayer every day. He always said “lead us not into Penn Station.” He never knew his daily error. I believe in him because asking protection from such places makes more sense to a child than fending off whatever “temptation” is. When I am a very young boy, my parents take me through the old Pennsylvania Station in New York City. Awesome and scary place; huge beyond belief; alternately chaotic and hauntingly empty; noisy, then silent. Strange sounds echo from far off. I think of that day whenever I see the 1931 Dracula. Doomed Renfield, looking like a beleaguered commuter who has missed the last train home, enters the cavernous halls of Castle Dracula, wondering what to do next.

I believe in the Penn Station boy because I see someone like him every day. He takes various forms. The two most common incarnations through most of my early years are Stan Laurel in airings of his 1930s comedy shorts and Lou Costello in reruns of his television series. They try to imitate the world as best they can, never really figuring it out, never quite getting it right. In every show, they do something akin to confusing “temptation” with “Penn Station.” Hilarious but spot on. As a child, and now often enough as an adult, I have exactly the same experience every day.

The Lord’s Prayer, via a Supreme Court ruling on prayer in public schools, and the old Penn Station, via relentless urban development, disappear from my life at about the same time. By then, both had done their job, exposing me to old world eloquence and elegance, to the power of words and image, of sight and sound. I may not have appreciated what I was saying or what I was seeing, but the memories are still with me.

* * *

Young thoughts often masquerade as old memories. Stories, especially family stories, may be told and retold so often that what are remembered are not actual events but retellings of them. I am certain that four ancient memories from my earliest years are recollections of what really happened. All relate to television and the movies. The first is perhaps my earliest memory. The second and third involve simple terror: once in a movie theater, once home watching television. The last memory is of a love story with, for young viewers, a good dose of primal fear.

* * *

Memory #1: I am in a stroller in my home town, Hoboken, New Jersey. Probably three years old, maybe still two. The weather is cold and crisp, and Momma has dressed me in a navy blue coat with matching hat. The hat is the key to the memory. Momma and Grandma are walking from Washington Street, the shopping avenue, to our apartment on Jefferson Street about five blocks away. In what may be the first abstract association of my life, I see a parallel between me in my stroller and one of my TV heroes.

My heroes at the time are cowboys on television: Lash LaRue, Hopalong Cassidy, The Lone Ranger, The Cisco Kid, and many others. Westerns saturate television, and thus my life. Short films from the 1930s and 1940s, stacked with commercials, fit well into TV time slots, and fill my Saturdays. Many of them end with a wild chase: good guys pursuing bad guys. One of my good guys—I forget who—rides with particular abandon. So as not to lose his hat, he grips it hard, waves it with gusto, and slaps it again and again across his galloping horse’s rump. To me, the moment is magic: freedom with resolve, daring with purpose, being grown up and playing like a kid at the same time.

While being wheeled home, I conjure that image, grab my hat, and wave it over my head with all the flamboyance that my little arm can muster. I slap it on the side of my stroller. The hat falls to the street pavement; Momma picks it up, brushes it off, puts it back on my head, and ties the hat’s strap under my chin. I repeat my performance, and so does Momma. Again the hat is in the street, and again Momma puts it back on my head. One more time with feeling, I wave the hat. Momma straps it tightly under my chin. Rather too tightly. After three trips to the gutter, the hat is rather wet, and I remember its cold, moist strap digging into the soft flesh under my chin. That unpleasant feeling is perhaps why the memory never leaves me. I know from my television viewing that pain is part of heroics. Part of the wild race toward revenge and justice with my hero, chasing down those bad men with dark horses and darker intents. If only Momma would push the stroller faster.

Over the years to come I often fantasize being my TV and movie heroes, from Mickey Mantle to Davy Crockett to Superman to Bela Lugosi’s mad doctors. But a forgotten cowboy wildly waving his Stetson becomes my first remembered fantasy.

* * *

Memory #2: Among the happiest times of my youth is September 1952 to September 1955: I am not old enough for school; my brother is, and so I have Momma all to myself during the day. I never want a lot of people around, and Momma provides all the company that I need. She usually keeps busy around our apartment while I play and watch television. She allows herself few indulgences. The only time that I remember her stealing a few hours to do something outside her routine is to catch an early matinee of War of the Worlds.

War of the Worlds opens to great success in late summer 1953. In those days, movies premier first in the big cities, and hit the smaller venues only after completing first runs. A box office hit needs some weeks to reach the Fabian Theater in Hoboken. So, Momma takes me to the movies after lunch sometime in the fall. I am three years old. It is a cool day, and I might be wearing the same blue coat and hat.

The movie begins with what seems to be a meteor hitting the earth. A probe emerges, and zaps a few curious locals. I scream and cry. Momma tries to calm me down, but the movie piles on the horrors. A well-meaning pastor is obliterated, and then an entire army unit. As its commander dissolves to nothingness, his skeleton is briefly visible before it disintegrates. Humanity’s destruction is well under way, and I am terrified. But not petrified, for I continue screaming. I know that I must stop, but cannot; so I turn my face to my seat, and dig my teeth into it to muffle my screams. My tongue laps the fabric. It tastes of dried soda and stale popcorn. The sensation is not pleasant, but it is oddly calming: the shot of reality that I need to know that the private world of my movie seat will protect me if I stay in it. Years later, watching boxing on television, I see a downed fighter lick the canvas, and I know why. The gritty taste brings him out of his punchy neverland, and back to the real world. I hide in my seat for the rest of the movie: 67 more minutes to go. An eternity for a young child, but I do not look at the screen again, and do not raise my head until the war of the worlds is over, and the houselights come up.

Momma will tell the story of that afternoon many times. For a few years, it is her excuse for not letting me see on TV or in the movies anything that might be scary. Sometimes, Momma uses the tale as an example of the futility of breaking her daily routine. Whatever the context, I do not welcome the retellings. In my first encounter with evil, I fail miserably.

Momma tells another story about War of the Worlds. In 1938, Orson Welles staged a great hoax by convincing radio listeners that Martians had landed in New Jersey. The whole episode is over before she and her immediate family in Jersey City know about it. Not so Momma’s uncle living in rural Pennsylvania. My great uncle grabs his gun and scours the hills looking for any aliens that might have landed a little off target. From my earliest days I hear the story, which I fully believe and still do. The few photos of Momma’s Pennsylvanian relatives in the family album show mountain men with rifles, posing next to horned bucks that they had just killed. I meet this uncle only once, long after 1953, and slowly realize that the benign, jovial old man is the same wiry mountaineer that I have always envisioned: rifle in hand, chaw in mouth, tattered hat on his head, traipsing the Alleghenies beneath a hunter’s moon for extraterrestrial game, ready to string up his kill for a photo. He looked evil in the face. I turned away.

I do not see War of the Worlds again until my late teens when it airs on television. Momma again tells the story of that terrible afternoon in 1953, but I cannot grasp at all what frightened me so. Now, after having raised two sons and appreciating what scares little boys, I can indeed. For the young, the line between reality and fantasy is easily crossed. A three year old can try repeating “it’s only a movie, it’s only movie,” but a well-crafted film brushes such reassurances aside. War of the Worlds starts with news footage of War World I, followed by even worse clips of War World II, and then the warning that the next war will be even more horrifying. “War of the Worlds” then fills the screen in blood red letters. The Martians’ first victims are not the cocksure army officers, the thoughtful scientist, or the sagely pastor—all as alien to my everyday life as the Martians themselves. First blood comes instead from an immigrant farmer, a wheeler-dealer out to make a buck off the new arrivals, and a naïve young man out for some excitement. They are people that I might meet any day. They might be my family. They might be me.

* * *

Memory #3: On a weekday afternoon, I am watching television alone in the living room of our apartment. I am four years old, about a year older than when I screamed and sobbed through War of the Worlds. My brother is outside with his friends. Pop is not home from work yet. Momma is in the kitchen preparing dinner. “In the kitchen” is at most 15 feet away, but Momma is not to be disturbed while cooking. I am quite alone. On television is Flash Gordon. Flash listens as a quivering, traumatized scientist tells of his harrowing experience. The screen cuts to his flashback: a death ray sweeps across a cave, killing everyone it touches. Three scientists bite the dust; only the narrator escapes to tell his tale. He does so very well, for I am spellbound and want no part of the ray. Flash, Dale Arden, and Dr. Zarkoff return to the cave. The ray searches for them. I jump from its path and land on our sofa. The ray turns in my direction, and I duck behind the sofa’s heavily upholstered arm. The scene is over and I, like the adventurers, survive. I hope that I will never see that ray again.

Not too long thereafter I do want to see the ray again, but half a century passes before I can. For most of those years I believe what I have seen is an episode from a Buster Crabbe Flash Gordon movie serial from the 1930s. I eventually see them all, a combined total of 42 episodes. Death rays do appear, but not the one that I remember so vividly. I wonder if my memory is a concocted fantasy.

What I saw is an episode of the short-lived Flash Gordon television series of 1954–55. As with War of the Worlds, my second viewing of “Planet of Death” (the episode’s title), more than 50 years later, conjures none of the deep fear of the first. Camera angles and lighting conceal the cardboard sets, and the actors do their best with the script. However much I might criticize the show, it hooked me and has never let go. Today, long after anyone who worked on the program has forgotten it, I have not.

* * *

Memory #4: In my youngest years, I do not follow the storylines of most of the television shows that I watch. Television is simply a series of unrelated sequences: gunfights and chases, broad slapstick and absurdist humor on kid’s comedy shows, broader and more absurd antics in cartoons. Why characters do what they do does not interest me. When they explain the action, I usually turn to my toys. Sometimes, I still do. I will play a movie that I have seen many times, ignore it while I putter with my paperwork, and pay attention to the screen only when the “big” scenes come.

Following the plot starts with a sentimental love story. Walt Disney’s weekly television series debuts in 1953, and sometime later the show airs a 1946 cartoon, Johnny Fedora & Alice Bluebonnet. I remember the plot perfectly:

Johnny and Alice are hats in a store window, very much in love. They are sold to customers who go separate ways. Johnny leaps from his owner’s head to find Alice. Run over by traffic, fought over by dogs, blown through a freezing winter, Johnny is then swept into a gutter and washed into a sewer. A trash collector retrieves him, cuts two holes in his brim and plops Johnny on a horse’s head. But the wagon’s other horse is wearing Alice. The lovers are reunited.

I remember the story less for its love-conquers-all theme than for its sense of loss and homelessness. Loss of home, and its twin horror, loss of parent, terrify children. The outside world is immense and unknown, but Johnny plunges boldly into it to regain his love. Will I be as courageous when life so challenges me? I might not remember Johnny’s story but for its surprise ending. Are Johnny and Alice reunited by chance or fate? Does destiny reward Johnny for enduring terrible hardships and never surrendering? What about Alice? What did she do to earn a happy ending? I wonder if her story will be the next cartoon.

By age five I will see a lot of Walt Disney animated movies: Snow White & The Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, Dumbo, Pinocchio, Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland. All of them have a good dose of loss of home and parent. The only one that stays with me, that I recall in detail, is a harrowing tale of a lost boy desperately searching for his father. Disney’s Pinocchio is best remembered for the puppet boy’s encounter with the whale Monstro and for Pleasure Island, where bad boys who behave like jackasses become them. For me terror comes earlier in the movie, when Pinocchio is led astray on his way to his first day at school. A few lies lead him into a hellish world. He spends the rest of the movie trying to return home.

At age five, I know that deceit exists, and that happiness and security are always at risk. I feel woefully ill equipped to combat the threats. My reflex is to nip the threat early by pretending to be more savvy and worldly than I am. Do I fool anyone? Probably not, but I fool myself, and that is the better part of courage.

About 10 years after my first encounter with Johnny Fedora, I discover the classic monsters of 1930s and 1940s horror movies. None of them scare me. Perhaps part of my fascination is that they are eternally homeless. They are Johnny Fedoras never plucked from the gutter, but returning with fearsome new powers and unsated desires. They are embodiments not only of childhood fears, but of childhood itself. What are Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and King Kong but hellish incarnations of Peter Pan, Pinocchio, and Dumbo? The Wolf Man and the other were-beasts of horror movies replace the countless talking animals in Disney cartoons. How far is the voyage from Pleasure Island, where bad boys become beasts, to the Island of Dr. Moreau, where innocent beasts become men?

This book is about that journey, with many stops on the way.